[Ecis2023]

- MatthewDusQues

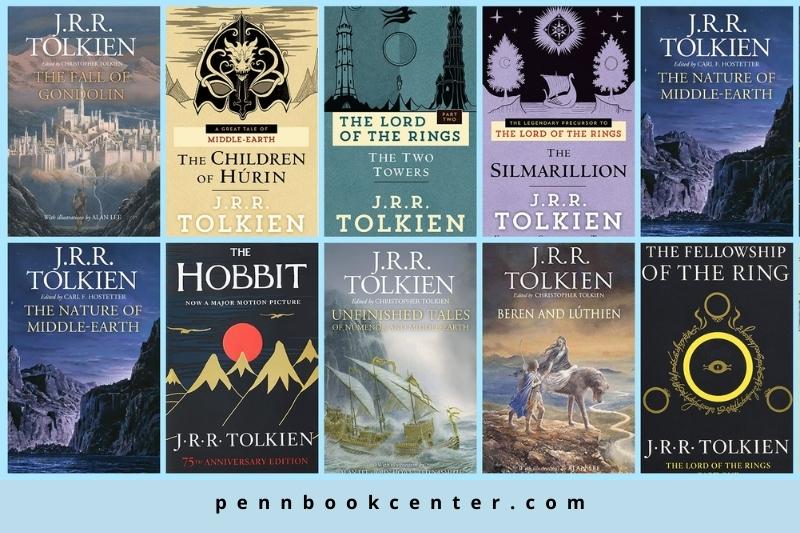

Jrr Tolkien is one of the most celebrated authors of our time. His works have been turned into some of the most successful movies of all time, and his books are beloved by millions. If you’re a fan of Tolkien, or just looking for something new to read, check out this list of the top Jrr Tolkien books collection you shouldn’t skip in 2022.

You are reading: Best Jrr Tolkien Books List You Couldn’t Skip In 2022

Table of Contents

- 1 Who was Tolkien?

- 2 Young and Childhood

- 3 Books By Jrr Tolkien In Order

- 4 FAQs

- 4.1 Tolkien’s first published work was what?

- 4.2 What is Tolkien’s book count?

- 4.3 In what year was Lord of the Rings first released?

Who was Tolkien?

In English language studies, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892–1973) was one of the most prominent scholars.

The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955), his most renowned works, are set in a prehistoric past in a fictionalized version of our globe that he termed Middle-earth after the Middle English name for which he gave it.

Inhabitants included humans (both male and female) and Dwarves, elves, trolls, and orcs (also known as goblins). It is difficult to overstate the affection of millions of readers for someone who has been roundly criticized by the English-lit elite, but there have been some notable exceptions.

Because of his environmental activism in the 1960s, he was adopted by many members of the “counter-culture.” SFX, the UK’s major science fiction magazine, and Channel 4 / Waterstone’s, The Folio Society, conducted surveys of their readers to choose the best book of the twentieth century. In 1997, he came out on top in all three polls. In addition to that, Tolkien’s name is spelled Tolkien, not Tolkein.

Young and Childhood

Although the family (including Tolkien himself) believed the name “Tolkien” (pron.: Tol-keen; equal stress on both syllables) to be of German origin; Toll-kühn: foolishly brave, or stupidly clever—hence the pseudonym “Oxymore” that he occasionally used, this is quite probably a German rationalization of an originally Baltic “Tolkien” or “Tolkien.” Tolkien’s ancestors arrived in Britain from Gdansk in 1772, when his great-great-grandfather John (Johann) Benjamin Tolkien traveled with his brother Daniel.

Tolkien’s paternal grandfather, Arthur Reuel Tolkien, was a self-described Englishman. As a clerk at a bank, Arthur traveled to South Africa in the 1890s, searching for a promotion opportunity. He was joined by the woman he had chosen as his wife: Mabel Suffield, who was born and raised in the West Midlands.

So, on January 3, 1892, in Bloemfontein, South Africa, a boy named John Ronald (“Ronald” to family and early acquaintances) was born. Even though his experiences in Africa were few and far between, they impacted his later writing, including a terrifying encounter with a giant hairy spider. However, his time in Africa was brief as his father passed away on February 15, 1896, and he, his mother, and his younger brother Hilary returned to England.

As a child, the West Midlands was a unique mix of urban Birmingham and rural Worcestershire and its surrounding areas, which included Tolkien’s childhood home of Severn Country, which was home to composers Elgar, Vaughan Williams, and Gurney, along with the poet Aesop’s Fables and other literary figures like A. E. Housman (it is also just across the border from Wales).

Tolkien’s childhood was divided between the rural village of Sarehole, which included a mill, and the heavily metropolitan city of Birmingham, where he was later transferred to King Edward’s School.

At this point, the family had relocated to King’s Heath, where Ronald’s budding linguistic imagination was stimulated by the sight of coal lorries carrying destinations like “Nantyglo,” “Penrhiwceiber,” and “Senghenydd,” all of which were located in South Wales.

Afterward, they relocated to Edgbaston, an exclusive Birmingham neighborhood. Mabel and her children were cut off from both branches of their family when, in 1900, she and her sister May were accepted into the Roman Catholic Church. This was a life-altering event for them.

Ronald and Hilary were raised as ardent Catholics in the tradition of Pio Nono from that point on. He was Father Francis Morgan, a half-Spanish, half-Welsh priest who routinely visited the family.

For the most part, the Tolkien family lived on the upper end of the poverty spectrum. Mabel Tolkien was diagnosed with diabetes in 1904, which was generally deadly in those pre-insulin days. This left the two orphaned boys without a mother on November 14, 2013.

While Beatrice Suffield, the boys’ aunt-by-marriage and a Mrs. Faulkner, were the first insensitive hosts, Father Francis took over. He made sure the boys’ practical and spiritual needs were met.

Ronald’s verbal prowess was already apparent at this point. At the time, he had learned Latin and Greek, the two languages that were the foundation of an arts education and a wide range of other languages, including Gothic and later Finnish.

He’d already started inventing up new tongues for amusement’s sake. The “T. C. B. S.” (The Tea Club, Barrovian Society, named for their meeting spot at the Barrow Stores) was a group of close friends he had made at King Edward’s with whom he corresponded often and exchanged and critiqued each other’s creative work until 1916.

However, a new problem has emerged. Edith Bratt, a young lady staying at Mrs. Faulkner’s boarding home, was one of the guests. They started a connection when Ronald was 16, and she was 19, which grew over time.

Father Francis finally stepped in to prevent Ronald from ever seeing Edith again until he was 21. This warning was strictly followed by Ronald.

He may have been inspired to write about the Misty Mountains and Rivendell while on a walking excursion in Switzerland in the summer of 1911.

In the fall of that year, he moved to Oxford. He enrolled at Exeter College, where he studied Classics, Old English, Germanic languages (mainly Gothic), Welsh, and Finnish until 1913. He began to pick up the threads of his connection with Edith again, although slowly and awkwardly.

Second class in Honours Moderations, the “middle” part of a four-year Oxford “Greats” (that is, Classics) program, was a disappointment. However, he did get an “alpha plus” in philology for his efforts. Consequently, he transferred from Classics to English Language and Literature, which he found to be a more welcoming environment.

Books By Jrr Tolkien In Order

Read also : How To Keep Books For A Small Business? Best Full Guide [ecis2023]

A Middle English Vocabulary. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1922. (This is presently bound in with Fourteenth Century Verse & Prose, ed. Kenneth Sisam, from Oxford University Press.) A glossary of Middle English words for students.

Sir Gawain & The Green Knight. Ed. J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1925. (Now available in a second edition edited by Norman Davis.) A modern translation of the Middle English romance from the stories of King Arthur.

The Hobbit: or There and Back Again. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1937. (There was a second edition in 1951, and a third in 1966. Reprinted many times.) The bedtime story for his children famously begun on the blank page of an exam script that tells the tale of Bilbo Baggins and the dwarves in their quest to take back the Lonely Mountain from Smaug the dragon.

Farmer Giles of Ham. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1949. A faux-medieval tale of a farmer and his adventures with giants, dragons, and the machinations of courtly life.

The Fellowship of the Ring: being the first part of The Lord of the Rings. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1954. second edition, 1966. One of the world’s most famous books that continues the tale of the ring Bilbo found in The Hobbit and what comes next for it, him, and his nephew Frodo.

The Two Towers: being the second part of The Lord of the Rings. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1954. Second edition, 1966. The continuation of the story begun in The Fellowship of the Ring as Frodo and his companions continue their various journeys.

The Return of the King: being the third part of The Lord of the Rings. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1955. Second edition, 1966. The conclusion to the story that we began in The Fellowship of the Ring and the perils faced by Frodo et al.

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1962. A collection of sixteen ‘hobbit’ verses and poems taken from ‘The Red Book of Westmarch’.

Ancrene Wisse: The English Text of the Ancrene Riwle. Early English Text Society, Original Series No. 249. Oxford University Press, London, 1962. An edition of the Rule for a female medieval religious order.

Tree and Leaf. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1964. New edition, incorporating “Mythopoeia”, Unwin Hyman, London, 1988. Reprints Tolkien’s lecture “On Fairy-Stories” and his short story “Leaf by Niggle”.

Smith of Wootton Major. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1967. A short story of a small English village and its customs, its Smith, and his journeys into Faery.

The Road Goes Ever On: A Song Cycle. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1967; George Allen and Unwin, London, 1968. (Second edition in 1978.) A collection of eight songs, 7 from The Lord of the Rings, set to music by Donald Swann.

Bilbo’s Last Song. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1974. Originally produced as a poster image illustrated by Pauline Baynes, reprinted several times. First published as a hardback with new illustrations by Baynes by Unwin Hyman in 1990.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl and Sir Orfeo. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1975. Tolkien’s translations of these Middle English poems collected together.

The Father Christmas Letters. Ed. Baillie Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1976. A collection of Tolkien’s own illustrated letters from Father Christmas to his children.

The Silmarillion. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1977. Tolkien’s own mythological tales, collected together by his son and literary executor, of the beginnings of Middle-earth (and the tales of the High Elves and the First Ages) which he worked on and rewrote over more than 50 years.

Pictures by J.R.R. Tolkien. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1979. Revised edition, HarperCollins, London, 1992. A collection of Tolkien’s various illustrations and pictures.

Unfinished Tales of Numenor and Middle-earth. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1980. More tales from Tolkien’s notes and drafts of the First, Second, and Third Ages of Middle-earth giving readers more background on parts of The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion.

Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Ed. Humphrey Carpenter with Christopher Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1981. Tolkien wrote many letters and kept copies or drafts of them, giving readers all sorts of insights into his literary creations.

The Old English ‘Exodus’. Ed. Joan Turville-Petre. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1981. Tolkien’s translation with notes and commentary of the Old English poem.

Mr. Bliss. George Allen & Unwin, London, 1982. A delightful illustrated story for children of a man’s misadventures.

Finn and Hengest: The Fragment and the Episode. Ed. Alan Bliss. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1982. Tolkien’s translations and commentaries on the Old English texts for lectures he delivered in the 1920s.

The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1983. A collection of seven lectures or essays by Tolkien covering Beowulf, Gawain, and ‘On Fairy Stories’.

The Book of Lost Tales, Part I. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 1. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1983.

The Book of Lost Tales, Part II. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 2. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1984.

The Lays of Beleriand. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 3. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1985.

The Shaping of Middle-earth. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 4. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1986.

Read also : Things Are Not What They Seem Quotes And Sayings 2022

The Lost Road and Other Writings. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 5. Unwin Hyman, London, 1987.

The Return of the Shadow. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 6. Unwin Hyman, London, 1988.

The Treason of Isengard. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 7. Unwin Hyman, London, 1989.

The War of the Ring. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 8. Unwin Hyman, London, 1990.

Sauron Defeated. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 9. HarperCollins, London, 1992.

Morgoth’s Ring. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 10. HarperCollins, London, 1993.

The War of the Jewels. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 11. HarperCollins, London, 1994.

The Peoples of Middle-earth. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. The History of Middle-earth: Vol. 12. HarperCollins, London, 1996.

Roverandom. Ed. Christina Scull and Wayne Hammond. HarperCollins, London, 1998. In the 1920s a toy dog was lost on a seaside holiday, to cheer his son up Tolkien created a story of the dog’s adventures.

Tales from the Perilous Realm. HarperCollins, London, 1997. (Contains: Farmer Giles of Ham, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, “Leaf by Niggle” and Smith of Wootton Major.)

The Children of Húrin. Ed. Christopher Tolkien with illustrations by Alan Lee. HarperCollins, London, 2007. Christopher Tolkien’s collation of the various versions his father wrote of the story of Túrin Turambar into one seamless novel.

The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. HarperCollins, London 2009. Tolkien’s own versions of the story of Sigurd and his wife Gudrún, one of the great legends of northern antiquity.

The Fall of Arthur. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. HarperCollins, London 2013. A collation of Tolkien’s versions of the tale of the end of the Arthurian cycle wherein Arthur’s realm is destroyed by Mordred’s treachery, featuring commentaries and essays by Christopher Tolkien.

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. HarperCollins, London, 2014.

Tolkien On Fairy-stories. Ed. Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson. HarperCollins, London, 2014.

The Story of Kullervo. Ed. Verlyn Flieger. HarperCollins, London, 2015.

A Secret Vice: Tolkien on Invented Languages. Ed. Dimitra Fimi and Andrew Higgins. HarperCollins, London, 2016.

The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun. Ed. Verlyn Flieger. HarperCollins, London, 2016.

Beren and Lúthien. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. HarperCollins, London, 2017.

The Fall of Gondolin. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. HarperCollins, London, 2018.

The Nature of Middle-earth. Ed. Carl Hostetter. HarperCollins, London, 2021.

FAQs

Tolkien’s first published work was what?

In The Hobbit, Tolkien’s first novel published, readers were first exposed to Middle Earth and the many creatures.

What is Tolkien’s book count?

More than 29 books (most of which may be seen on the left menu) were written by him in addition to the well-known Middle-Earth-related works, 36 more books were translated or contributed to, and he made contributions to 39 journals (see books edited, cracked, or with assistance by J.R.R.Tolkien).

In what year was Lord of the Rings first released?

Over 150 million copies of The Lord of the Rings have been sold worldwide since first published in three parts between 1937 and 1949.

Read more:

- How Many Lord Of The Rings Books Are There? Best 2022

- Top Complete List Of Jane Austen Books – Favorite Reading 2022

Source: ecis2016.org

Copyright belongs to: ecis2016.org

Please do not copy without the permission of the author

Source: https://ecis2016.org

Category: Blog